This is a repost of a blog written a few years ago. I was surprised at how many people I know that don’t have a direct relationship with a scientist. Cloaked ostensibly in white lab coats (or more likely covered in sediment with hip waders), scientists are a mystery. Like so many other issues in our lives, the success in using science– with other considerations in decision- making– rests on relationships.

It would be wonderful to develop a muscle for more casual workgroups that include decision-makers, communicators, creatives, and scientists.

I work as a bridge between scientists and other technical professionals and the wide world of other skilled people. Collectively, we try to solve problems so we live in a more resilient, safe, beautiful, and healthy place. The problems are vexing and the interests are all over the map but we are committed to evidence-based decision making– that’s a good thing.

As technical professionals, we want our science-based information to be used in policy development. There is no doubt that science is used in policy development but the process is not as direct or compelling as we would like or assume.

Scientists are often driven to conduct research connected with their fields, which raises novel questions or may be connected with funding availability. We need to consider how research answers questions that policymakers need to inform their decisions or provide a rational basis for the choices they make. Our research has definite policy implications but there may be room to do more upfront planning with policy-makers.

A policy is a deliberate system of principles to guide decisions and achieve rational outcomes. A policy is a statement of intent decision-makingand is implemented as a procedure or protocol. Policies are generally adopted by a governance body within an organization. Policies can assist in both subjective and objective decision making. Policies to assist in subjective decision making usually assist senior management with decisions that must be based on the relative merits of a number of factors, and as a result, are often hard to test objectively, e.g. work-life balance policy. In contrast, policies to assist in objective decision-making are usually operational in nature and can be objectively tested, e.g. password policy.[1]

The term may apply to government, private sector organizations, and groups, as well as individuals. Presidential executive orders, corporate privacy policies, and parliamentary rules of order are all examples of policy. Policy differs from rules or law. While the law can compel or prohibit behaviors (e.g. a law requiring the payment of taxes on income), policy merely guides actions toward those that are most likely to achieve the desired outcome [Wikipedia].

There is a wide range of ways in which scientists and allied professionals undertake scientific research. Most of the scientists we work with or employ are tacitly related to the public policy enterprise. This means that their scientific results are being used to inform policies, incentives, laws, or to tell cautionary tales about our near future. Stories of science should reveal the unrevealed, offer opportunities to address issues, lift the spirit and connect with everyday life.

Barriers

One notable threshold barrier to connecting science to policy is that we often don’t know much about our policymakers. Who are they? At what scale do they operate? What are their operational constraining factors? What do they consider when making decisions? (See Connecting Science, Policy and Decision-Making, NOAA Office of Global Programs),

Based on formative research by NOAA’s Office of Global Programs, we developed a shortlist of questions for “decision-makers.” Decisions can be operational, strategic or tactical in nature. Decisions occur at all levels and scales, from staff-level operations to major policy declarations and changes in the law.

The Continuum of Thinking on the Science-Policy Interface

Long-held beliefs, much like the deficit model of environmental “education” or sharing, are predicated on the assumption and/or nominal evaluation of science-policy interactions based on science’s credibility, relevancy, and legitimacy. More recent evidence shifts this analysis to focus on ACTA: Applicability,

Comprehensiveness, Timing, and Accessibility.

One of the constraining factors identified by analysts from Australia was the lack of demand for the scientific research being generated, thus mimicking the gap between what we think is important vs. what is important to a priority audience—in this case, policymakers. Other related barriers identified were:

· The science was weakly contextualized and often failed to address real-world problems

· Organizational Culture

· Values and ethics

· Regulatory environment

· Resources

· Bargaining

· Entrenched commitments

· Constraints such as time, money, multi-faceted evidence needs

· Production of science information versus the demand for it

The author’s recommendations are to use the ACTA model to strengthen the science-policy interface which would, in essence, require a more integrated, up-front “co-creation” of science and policy as a braided concept and practice. Please note this does not preclude scientific endeavors that are generated independently from a policy domain.

Applicability

· Scale or “fit” the research to the policy problem

· Develop the research questions with policymakers in mind

· Bring solutions, not just problems

· Highlight opportunities (for partnerships, integrated thinking, job creation, innovation, expanding the people we work with)

· Develop an implementation strategy for the research once it’s published

· Include cost, engineering, maintenance, and management in the overall approach

· Engage and be open

Comprehensiveness

· Promote context by taking an interdisciplinary approach

· Look across departments

· Look at the life cycle of decisions and understand/apply the different evidentiary needs at each phase

· Look at costs, benefits, and risk– the business case (someone outside the scientist would need to do this work)

Timing

· Is there a way to speed the applicability of the science?

· Policymakers are often in a rush to find tools and implementation strategies- are there ways to take the findings and craft early phase tools?

· Pay attention to windows of opportunity- a policy often occurs in constrained windows of time

· Avoid producing the right answers at the wrong time, if possible

Accessibility

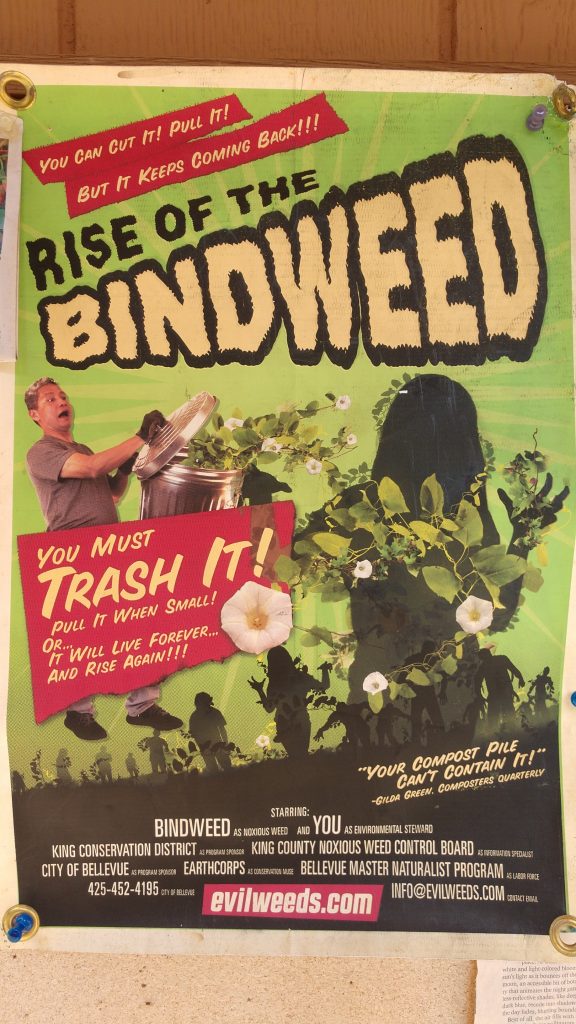

· Readable (plain language, an executive summary with major points, no jargon!)

· Intelligible to the specific audience (which requires that you know something about them)

· Sound bites, short points, key messages and images are all very helpful

· Work on addressing journal indexing which makes it difficult for policymakers to find the evidence they need

“Accessibility is a pre-condition of influence, as all other factors that might help or hinder research influence are moot if policy-makers cannot find or understand relevant research in the first place” (Newman et. al, Publ. Manage. Rev. 19(2), 157-174, 2016).

Researcher Susan Mason from Boise State University interviewed a wide swath of federal, state, and local officials regarding their use of science in policy and found the following:

• Policymakers believe there are instances in which science provides answers to specific policy problems (83.3%).

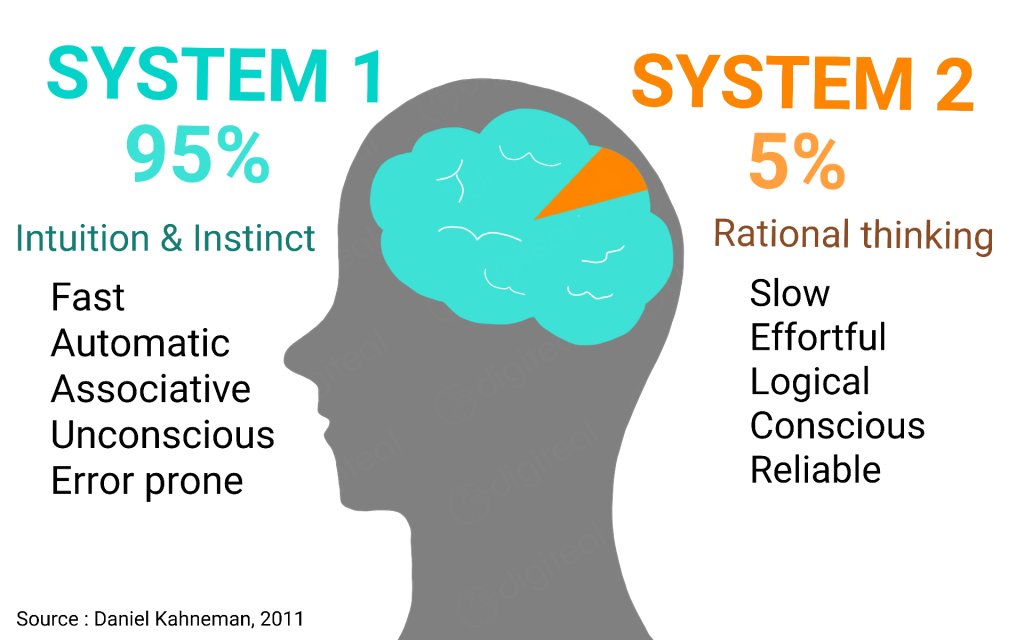

• Policymakers view science as different from other ways of knowing because the processes are testable, empirical, replicable, peer-reviewed, and not intuitive (86.6%).

• Policymakers believe that it is important that their policies be supported by science (80%).

• Policymakerspolicy-making use science in all three stages of the policy-making process (70%).

• Policymakers obtain their information from a variety of sources, and a majority stated government agencies as at least one source (60%).

• Policymakers believe that there are areas in which science is viewed to be more important to public policy because of the nature of the issue (80%).

• Policymakers, decision-making stated that more than 17 factors influence public policy decision-making. Of those factors, respondents indicated that 46% of the time politics was a factor, and 53% of the time capacity to implement the decision, including the cost and funding, was a factor of influence.

• Policymakers stated that 75% to 100% – of the time their decisions are founded on science (50%).

Tid-Bits about Elected Officials

· They rely on agency-level data and consultants

· Reported that science helps them in all phases of decision-making

· Do not collect their own primary data (compared to non-elected officials)

· Financial capacity was a contributing factor to policy.

[Decision Making at the State and Local Level: Does Science Matter? PS: Political Science & Politics, published by Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/S1049096515001183

Local Example: Use of Science by Local Integrating Organizations (LIOs)

The Puget Sound Partnership (PSP), with funding from EPA’s National Estuary Program, partially funds the operations of regionalized groups of partners as Local Integrating Organizations or LIOs. These groups work, in part, to support the roadmap for Puget Sound recovery called the Action Agenda, in addition to their related policy and on-the-ground work.

In 2017, Tom Koontz from the University of Washington-Tacoma surveyed how LIOs used science in developing their ecosystem recovery plans. The interviewees rated the applicability and credibility of scientific studies themselves as important factors for using science. Previous research indicated that science was used in three primary ways: (1) Instrumental (cause and effect designations); (2) Conceptual (science informs policy in a loose way); or (3) symbolic (science is used post facto decision making to justify the decision).

Factors influencing the Ecosystem Recovery Plans included what stakeholders want, scientific or technical information from outside the Puget Sound Partnership, local time and place-specific information, and networking outside PSP. The LIOs were also asked about the perceived influence of factors affecting the use of science in their plans:

In descending order, these factors are:

· Applicability of the information to the recovery plan objectives

· Credibility and prestige of the source

· Focus on variables for which management intervention is possible

· Whether it was recommended by an LIO member (peer influence)

· Ability to verify the quality of the research results

· Ease of comprehension

· Whether it was recommended by PSP

· Whether it was recommended by a consultant to PSP

An important underlying result was that science was used to understand phenomena but decisions didn’t directly refer to scientific research. Working with LIOs to illustrate how to cite scientific findings could be very helpful in the future.

Best Practices for Strengthening the Science-Policy Continuum

1. Consider upfront, integrated policy, and science planning

2. Understand and develop relationships with policymakers and those who influence them

3. Use Plain language for translation

4. Understand science in its complete context: finance, timing, politics, utility, interdependencies

5. Describe relevance and applied benefits all the time

6. Be yourself- tell stories

Heidi Siegelbaum, Communications at PNW-SETAC, Washington Stormwater Center, Stormwater Strategic Initiative Lead Team